2018 marks the seventeenth year of the partnership between Bristol and the city of Guangzhou (formerly Canton) in Guangdong Province Southern China. Located on the Pearl River about 120km north west of Hong Kong and 145 km North of Macau, Guangzhou has a history spanning 2200 years and was a major terminus for the maritime silk road and continues to serve as a major port and transportation hub today as well as being one of China’s largest cities. In 2016 a stainless-steel kapok flower sculpture that was donated by the Mayor of Guangzhou to the City of Bristol and now stands proudly in our Chinese Medicinal Herb Garden. Many people and business have links with Guangzhou and the University of Bristol has made a number of links with organisations across the city including the San Yet-sen University. On a visit in January 2017 to Guangzhou our Dean of Science Professor Tim Gallagher visited the South China Botanic Garden to make contact with scientists in the Chinese Academy of Science. An action from this meeting was for the South China Botanic Garden and the University of Bristol Botanic Garden to work more closely together. With this raison d’être in mind myself and Tony Harrison our Traditional Chinese Herb Garden co-ordinator and former Vice President of the Register of Chinese Herbal Medicine set off for China on the 11 April 2018. This was my first visit and Tony’s sixth to this vast country. We would only visit Guangzhou city with one day trip organised to the Yingde Mountains to meet tea growers and see first-hand the Yingde Karst stone landscape and visit its quarries.

Our trips had a series of key objectives:

- · To make a link between University of Bristol Botanic Garden and the South China Botanic Garden

- · Source new lotus Nelumbo nucifera cultivars to replace ones we have lost from our collection

- · Understand tea cultivation, observe tea being cultivated in the Yingde tea growing mountains, meet the growers and secure tea cultivars from central and northern provinces where the tea is more cold-tolerant

- · Obtain different species of turmeric and other members of the ginger family to add to our collection

- · Look at their medicinal herb collection and identify species that may be for merit to our

|

Myself and Tony with South

China Academy of Sciences |

collection in Bristol

- · To visit classical gardens of Guangdong including Qinghui Yu Jin Shan Fang and Liang Yuan gardens as models for our culture gardens at the University of Bristol, Botanic Garden

- · Exchange ideas with colleagues at the South China Botanic Garden

Guangzhou is not a city for the unseasoned traveller as the bustling busy streets teem with people and traffic and its rapid growth over the past twenty years has swallowed up its old centre, known around the world by its former name of Canton. Located in Guangdong Province, one of Chinese powerhouse provinces, the city is home to 13 million people. Most of these have migrated here from the countryside over the past twenty years in search of work, higher paid jobs and a less arduous working life than the agricultural villages of the rural Guangdong.

Everywhere tower blocks 30-40 stories high have sprouted up to accommodate the rising population. Early fast growth has morphed into more substantial buildings of glass and steel where offices now bustle with activity processing the wealth the province generates from its many factories that make many goods we enjoy in the West. The local inhabitants do not have any green space of their own as private gardens and allotments are not know. But large areas of often hilly ground set in what is otherwise a flat delta landscape surrounding the Pearl River are covered in indigenous forest. Many have temples, and most are accessible by a network of pathways and facilities that allow the population to us them for recreational sports, jogging, walking, reading and generally getting away from the noise of the traffic.

We based ourselves in the Baiyun district next to one of these green spaces Baiyun Mountain. This made an excellent rest bite and proved to be near to the South China Botanic Garden and the Chinese Academy of Science. Here we made contact with their senior scientific team, headed up by Professor Ying Wang a plant scientist and geneticist. As part of our discussions we gave a presentation on the development of the UBBG and how the garden is used for teaching by the School of Biological Sciences and our public engagement work. We met senior science staff including: Professor Xia Nianhe, chief taxonomist and national expert in Bamboos, Gingers and Magnolias, who has worked at the garden for 36 years and has been instrumental in developing a unique collection of Magnoliaceae in a 10-hectare (25 acre) part of the Botanic Garden, including the newly discovered Magnolia guangdongensis with its attractive copper coloured hairy undersides to its leaves, discovered on one mountain top in Guangdong Province. He has also developed a unique collection of ginger family Zingiberaceae, including species of ginger Zingiber, tumeric, Curcuma,Cardamon, (Elletaria & Amomum) and Galangal Kaempferia. This comprehensive collection is in a specially designed garden 1.2ha in size, (the whole of the University of Bristol Botanic Garden is only 1.7 ha).

|

Tony Harrison with colleagues from the

South China Botanic Garden

looking at the ginger collection. |

Associate Professor Lei Chen responsible for the aquatic plant collection, including over 100 cultivars of lotus, Nelumbo nucifera, Professor Xiaoyi Wei who researches natural product chemistry and Professor Ziyin Yang whose work into tea cultivation and phyto-chemistry is of national importance to China. Our hosts gave presentations of their work, which ranged from finding new plant chemicals to DNA finger printing wild population of rare Chinese Herbs and establishing ex-situ populations to develop agricultural business and so remove pressure on dwindling wild populations.

Professor Ziyin Yang was particularly interesting as his work on tea chemistry has lead him to study many different tea cultivars (in China there are many hundreds of tea cultivars). Soil type and position on mountain site and genetic composition all affect the chemical composition of the tea cultivar as the base ingredient of the tea making process. The chemical process that changes in the tea leaves during processing gives rise to the final polyphenol mix, giving that tea its individual character of aroma and taste. Later in the trip we travelled courtesy of tea buyer and exporter Jennifer Jiang to the Yingde mountain area. A two-hour drive north of Guangzhou we finally reach the home of the famous Yingde tea.

The climate is sub-topical and when we visited in the second week of April the wet season was starting. Everywhere thick mountain forest vegetation was bursting into life. This heavily mountainous region rises from flat river flood plains of sediments and rich soils. This is home of Yingde tea which is famous throughout China. Many cultivars are grown, but we meet a tea grower who grows a hybrid between a big leaved Ynnuan cultivar and a narassas cultivar known as ‘Large Leaved No.9’.

The tea character is Oolong and the most profitable cultivar is intriguingly called 1959, a blend developed and named in honour of our Queen Elizabeth’s state visit to China in that year. This high-profile blend which is sold in China commands a high price of £80 per kilo retail and £40 per kilo wholesale. After a couple of hours of tea tasting and discussion of processing we travelled to the plantation.

|

| Discussing tea cultivation. |

The trend in China is for more tea growers to grow in a sustainable way. Pesticide use in common in China a practice that became mainstream about fifteen years ago in a drive to increase food production. The result has been a short-term increase in food production, but at cost to the environment and a reliance on pesticide use that stays with the crops into the food chain. Pesticide residue in foodstuffs, including tea is proving a big problem as levels that do not meet European standards result in high quality tea not being able to be sold to the lucrative European market. In a move to change this some growers including the one we visited have moved towards sustainable tea growing.

A number of practices to help achieve this:

i) Cows are introduced to the tea plantation (they eat weeds, but not the tea as its tastes bitter). This keeps down the weeds. Some weeds are unpalatable and at the time of our visit a non-native species of Oxalis and a Persicaria with strong growth were being dug by hand with the aid of a mattock. Back breaking work, but necessary to avoid the use of weed killer.

ii) Extra nutrients are provided by collecting cow dung and rotting it down in large steaming heaps. This is a quick process in the sub-tropical climate, (temperatures on the day of our visit were 26’C, but this will rise to 36’C in summer with lots of rainfall and annual rainfall of 1700mm). After rotting down under a tarpaulin, the manure is placed in a tank for further rotting and the resulting liquid is syphoned off into another tank to be diluted down with water before being pumped onto the plantation by a series of sprinklers. The resulting nutrient spray increase growth by up to 50%.

iii) Trees are allowed to grow at higher density and a mixture of tree species are cultivated to attract different bird species. These trees provide safe roosting place and refuge whilst they make feeding sorties in amongst the tea plants.

iv) We saw tea five years old and new plants that were only in the soil for one month. The oldest plants were 50 years old and picking of the tea shoots was carried out once a year. 50% less than an intensive plantation where it’s done twice a year. The result is the plants are less stressed.

|

Cows are an important part of weed

control in a sustainable tea plantation |

One hours drive northwest of the tea plantation was the limestone karst region of Yindge, home to the famous Yingde stone. Yingde stone (limestone with calcite deposits) is famous throughout China for its water worn limestone full of character, particularly holes dissolved by acid rain over thousands of years. We visited Yingde Stone Garden built by the local tourist company where the most astonishingly beautiful pieces of stone are displayed in a large garden setting. The sizes of some the pieces dwarf visitors and resemble the individual stone sizes at Stonehenge or Avebury Circle, but with the difference of many pieces full of delicate holes. The obvious question of how these are quarried and transported without damaging each piece remained to us unanswered.

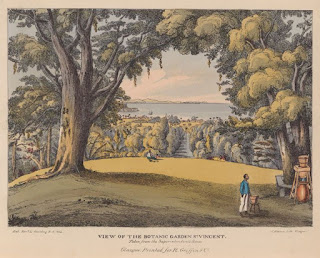

Everything in China is huge. The South China Botanic Garden is a whopping 333 ha (3.33 square

|

| Yingde stone piece |

kilometres) that’s 822 acres or just over twice the size of Clifton and Durdham Downs combined and even has its own Metro station. The Garden is flat with numerous lakes and pools. Its centre piece is a large glasshouse with climate-controlled zones, featuring tropical, subtropical and even a cool temperate region which is refrigerated. The standard of care and display of these collections was excellent. The South China Academy of Sciences located in the South China Botanic Garden and is one of a number of centres of excellence for research and technology. The Garden boasts 600 staff including 120 academics and its main focus is the flora of the South of China and the neighbouring countries of Loas, Cambodia, Vietnam and Thailand. Documenting and describing the 36,000 species of plant found in China has been a strategic focus over the past 40 years. A number of floras have been published and now an e-flora is available to all at here. After discussion we plan to have a memorandum of understanding between our two gardens and look forward to working with and share plant material as part of the ‘partner or sister city link between Bristol and Guangzhou’.

by Botanic Garden Curator Nick Wray