By Alida Robey

Nematodes pop up from time-to-time on gardening programmes, but usually as something of an afterthought: “Oh, and of course if you don’t want to use pesticides you can always try nematodes.” A certain air of mystique has surrounded nematodes for some years now, but these environmentally friendly pest controllers

warrant far more consideration than a mere afterthought!

Nematodes are in fact one of the most successful and adaptable animals on the planet. They are second only to the insects in their diversity of species, geographic spread and the range of habitats they can occupy. There are more than 15,000 known species of nematodes, more commonly known as roundworms, and likely thousands more that are yet to be described.

There are parasitic nematodes that live in the gut of animals, humans, birds and mammals. Other species are free-living in the soil, feeding on bacteria and garden waste. Some are parasitic on plants and may cause disease and crop devastation. But, as a gardener, I’m most interested in those species that are free-living in healthy soil and those that parasitise common garden pests.

Free-living garden nematodes are microscopic thread-like worms, which are scarcely visible without a microscope. (This is in marked contrast to the 9 metre long species,

Placentonemagigantissima, which can be found in the placenta of the sperm whale!). In good nutritious soil there could be as many as 3 billion individuals per acre. They eat fungi, bacteria and algae. So, much like ordinary earthworms, they have a useful role in decomposing and recycling nutrients.

Biological control with a specific target

Parasitic species have an equally important role in the garden. With such a diversity of species, it is not surprising to find that there are nematodes that specifically parasitise slugs, ants, vine weevil, leather jacket, chafer grub – you name it! This means that a slug nematode won’t have any impact on anything but slugs – this isn’t always the case with other biological controls and rarely the case with chemical controls.

|

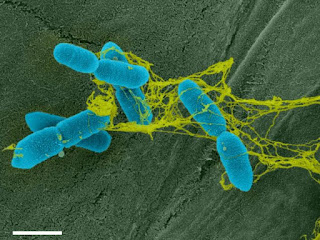

A wax moth pupa can be a host to thousands of

nematodes. The parasitised cadavers can be placed in

orchards to protect crops from pests such as citrus root and black

vine weevils.

Photo credit: Peggy Greb, US Department of Agriculture |

It works like this: the juvenile nematodes are in the soil looking for a specific host. Once found, the nematode enters the body of the host and gives off bacteria inside the host’s body. These bacteria multiply and cause blood poisoning and, eventually, death. The nematodes then feed on the body of the creature and multiply, sending a new generation off into the soil to find another host. When hosts are scarce, the nematodes naturally die off.

The practicalities of using nematodes

As nematodes are living organisms they have a very limited shelf life. They therefore need to be bought online, stored according to instructions and used very soon after delivery.

There are several UK suppliers of nematodes.

It is important to choose the correct nematode species for the right type of pest and to use them in the right conditions. The soil temperature has to be above 5oC (and remain so) and they should be applied only when the pests or their larvae are active. Nematodes are also light sensitive, so use them early morning or dusk, when light levels are low.

They come as a thick paste in a little sachet, which you need to dilute with water. Repeat applications may be needed.

The specifics:

Ants : Drench the nests between April and September.

Chafer grubs: Apply nematodes in August and early September.

Fruit flies, carrot root fly, onion fly, gooseberry sawfly and codling moth: All of these pests can be treated with a generic nematode mix called Nemasys Natural Fruit and Veg Protection Pest Control. You can use it as a general treatment after planting out and when the soil has warmed up, or to target specific pests when you see them, such as gooseberry sawfly caterpillars. These (and other caterpillars) need to have direct contact with the spray while they are on the leaves.

Leather jackets: These are the larvae of the crane fly or daddy longlegs and attack the roots of grass in the lawn. Treat with nematodes in the autumn, when the adult daddy-long-legs are laying.

Slugs: The nematode for slugs was discovered by scientists at the University of Bristol! An application early in spring will tackle the young slugs growing under the ground, which are feeding on humus. A single application should last for at least 6 weeks, which allows time for tender seedlings and young plants to get established. They can be applied until early Autumn.

If using on potatoes, apply them 6-7 weeks before harvesting , when the tubers are most likely to be eaten by slugs.

Slug nematodes are very efficient, enjoying the same wet environment so loved by the slugs themselves.

Vine weevils: An application in March will give much greater control of larvae when they are present – either March to May, or from July to October.

So in May 2017, we should see just how well this little creature stacks up against the chemical and other treatments in tackling arguably our most annoying garden pest.

Alida Robey has a small gardening business in Bristol. For several years in New Zealand she worked with others to support projects to establish composting on both domestic and a ‘city-to-farm’ basis.