Today as I write this the sun is shining, the birds are in full voice singing, cawing and screeching around the Garden. Bulbs are popping up, crocus are the first with daffodils a week away from carpeting the ground with yellow. Primroses are dotting grassy areas and bees are beginning to forage in the middle of the day; the minimum temperature that a bee can fly is said to be 13 degrees, so when you see one out and about you know the season is changing. In February in this part of the UK we get an extra two and a half minutes of light every day; after February and through March to June it is only two minutes. This is why a lot seems to change in February in the Garden, it is a conduit for spring; the end of January is incomparable to the beginning of March in terms of light, flower and the beginnings of warmth. We’ll still get ice, cold, wet and maybe even snow again between now and summer, but days like this make us feel that winter is nearly behind us.

In the Garden there are exciting changes happening. Our South African display has had the framework of a traditional African roundhouse present for much of last year; as I write this it is being thatched with a South African reed called Cape thatching reed; Thamnochortus insignis, the building will then be rendered in a red cob. These features are important for bringing context to the plants around it, being a talking point and attracting people to the Garden where they can leave with maybe a lot, maybe a little, but some new knowledge of the plant world that they didn’t have before.

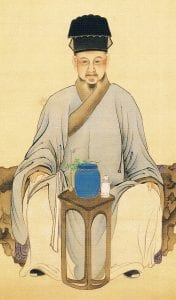

Another development is our Chinese tea plantation. Yes, a tea plantation here in Bristol, just a small one but a tea plantation none the less. When landscaping the area where we’ll grow tea, visitors ask what I’m doing and seem intrigued and interested with the response. Tea is something that is in the heart of UK people, many conversations, moments of relaxation, tears and laughter have happened over a cup of tea and many millions of hands have been warmed on a mug during winter. In China tea drinking dates back 5000 years. Legend has it that Emporer Shen Nung was boiling water when leaves from a wild tree blew into his pot; he was so interested in the aroma that he drank some. He named the brew ch’a, meaning to check or investigate. Tea became integral to the culture of China when Lu Yu, a Chinese scholar, dedicated his life to the study of tea; he wrote a treatise called ‘ The Classic of Tea’ in 760CE, the earliest work dedicated to tea. Today every Chinese household will have tea brewing sets and use tea brewing as a form of welcome, celebration, in family gatherings or to apologise. We’re looking forward to planting our fifteen (so far) Camelia sinensis plants; they should be in the ground by March, which, coincidentally, is when our refreshments open again after the winter…

We look forward to seeing you in the Garden, keep your eyes on the ground and enjoy early spring!